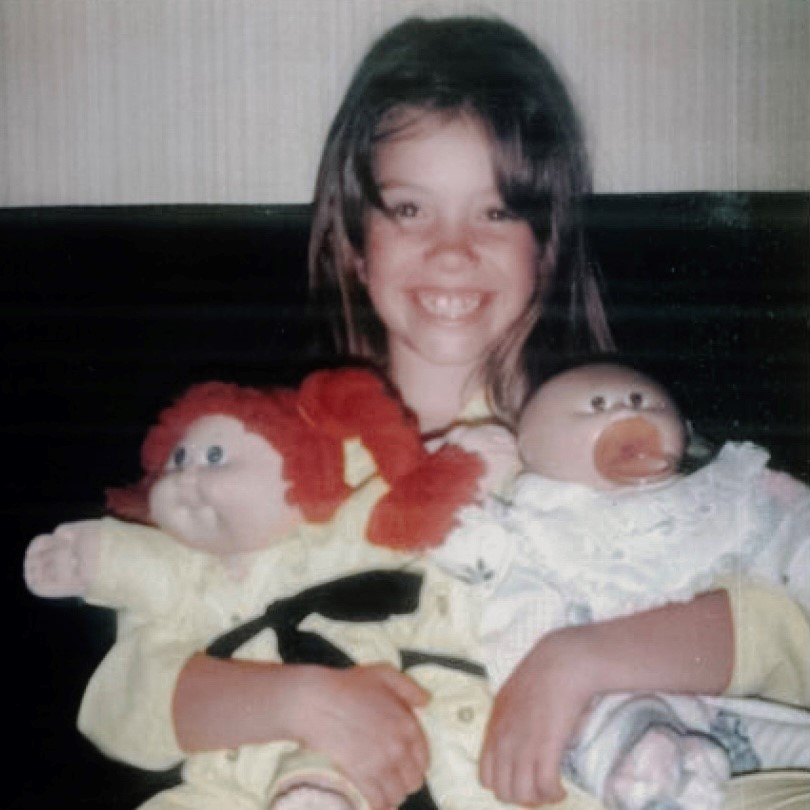

On July 30, 1985, at approximately 10:30 am, Morin went down to the lobby of her building to pick up the mail. She returned to the apartment to get ready for a planned swim date with a friend. The pool was located in the rear of their building complex. Before leaving the apartment, she spoke to her friend via the intercom and said she would meet her in the lobby shortly. She left the apartment at about 11 am wearing a peach-coloured, one-piece bathing suit, green hairband, and red canvas shoes; she carried a plastic bag containing a white T-shirt, green and white shorts, suntan lotion, hairbrush, a peach-coloured blanket and a purple beach towel.

Fifteen minutes later, the friend buzzed her apartment to ask why Morin had not met her yet. Nicole’s mother Jeanette, who was busy with small children in a daycare group that she ran in her apartment, assumed that Morin had gone to the pool herself or was playing with other children at the rear of the complex. She did not call the police to report her missing child until about 3:00 pm.

Investigation

The police investigation initially involved “active searches and canvassing” of all of the apartments in the complex. The first day, police set up roadblocks around the building and circulated vehicles with public address systems to alert neighborhood residents to the missing child’s description. Knocking on every door in Morin’s 429-unit complex, police entered apartments even if no one answered the knock. After a woman who lived in the building identified Morin from a photograph, police determined that Morin had travelled down the elevator and entered the lobby. From there, however, no other evidence was found as to Morin’s whereabouts.

The next day, additional Toronto Police Service officers were brought in, and a “police dragnet consisting of mounted horsemen, marine units, helicopters and foot patrols” began combing the area near Highway 27, which was in the vicinity of the apartment building. Tracking dogs were also brought in to explore the building’s underground garages, utility rooms, storage units, and sump pump rooms. A neighbor recalled seeing an unidentified blonde woman with a notebook on the floor that Nicole’s apartment was located on, about 45 minutes before the disappearance. Police sought her as a possible witness, but she was never identified, nor did anyone come forwards claiming to be her. More than 900 neighborhood residents joined the search. The newly formed Toronto Crime Stoppers organization took on the disappearance as its first significant case. This organization posted a $1,000 reward, printed posters, and produced a video re-enactment of Morin’s last known movements which aired on television several weeks later. The Toronto Star printed 6,000 copies of a poster showing Morin’s picture and the phone number of the Metro Toronto Police. Three thousand copies of a watercolour sketch of Morin were commissioned by the Toronto police and distributed to police departments, post offices, and local stores.

The search was the biggest missing-person investigation in the history of the Toronto Police Service. Toronto police formed a 20-member task force which remained active for nine months. They invested 25,000 man hours following up leads. By November, police had questioned about 6,000 individuals, including hundreds of sex offenders. The first year’s investigation cost an estimated $1.8 million. The police also offered a $100,000 reward for Morin’s safe return, a reward that is still applicable today.

Police cleared all family members and acquaintances from suspicion. An unexplained note was found in the apartment on which Morin had written in pencil a few months earlier: “I’m going to disappear”.

Although police discouraged it, Art Morin raised funds to hire a private investigator. He also left his job, set up an office, and searched for clues for his missing daughter in Canada and the United States. He moved back in with Jeanette after Nicole’s disappearance, but the couple permanently separated in 1987. Jeanette consulted with a psychic in Calgary in her own effort to locate her daughter.

In 2004, researchers for a Belgian organization known as Fondation Princesses de Croÿ et Massimo Lancellotti announced that they had tentatively matched photographs of Morin seen on a Canadian police website with pictures on a Dutch website that advocates for sexually-abused children. Using biometrical analysis, the researchers claimed a strong resemblance between Morin and a child in a pedophile network in Zandvoort.

Despite the years of investigations and thousands of leads, no physical evidence has ever been uncovered to solve the disappearance.

Ongoing efforts

While the case is considered a cold case, Toronto police and missing-child organizations continue to keep it in the public eye in an effort to garner fresh leads. Several video re-enactments of Morin’s last movements have been produced, including a 2007 television re-enactment for GTA’s Most Wanted. For the 29th anniversary of the disappearance in 2014, the Toronto Police Video Unit produced a re-enactment which was also screened at Mac’s Convenience Stores throughout the province of Ontario.

For the 30th anniversary of the disappearance in 2015, Toronto police organized a 5K run called Nicole’s Run at Centennial Park in Etobicoke. The event included a candlelight vigil. In addition to raising awareness of the case, the run collected $3,000 in donations for the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, which operates a missing-child website.

In 2019, on the 34th anniversary of the disappearance, the Toronto police’s missing-persons unit released an age-enhanced picture of Morin suggesting what she might look like in her early 40s.

In 2001, Toronto Crime Stoppers disseminated an age-enhanced photograph of Morin as a woman in her mid-20s to more than 1,000 Crime Stoppers programs in 17 countries via the internet. Child Find Ontario has also endeavored to maintain public awareness of the case by arranging for Morin’s picture, physical description, and age-enhanced photographs to appear “on electronic screens in Esso gas stations, billing envelopes from Rogers Cable and the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Toronto Transit Commission display screens, and on the back of transport trucks”.

Morin’s mother Jeanette died in 2007. Her father still lives in the Etobicoke area.